John Ashbery is briefly invoked in this review of a new poetry collection by Bernadette Mayer, a poet he greatly admired.

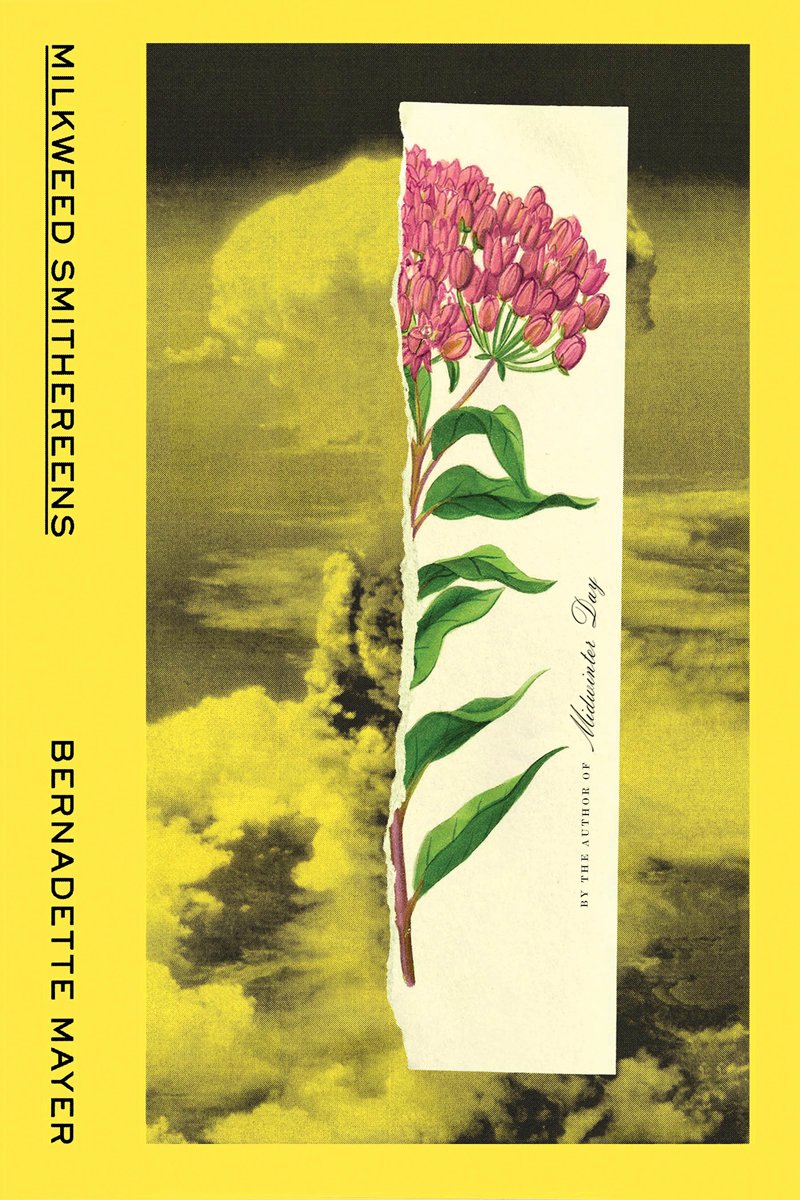

Milkweed Smithereens

Brian Dillon

From the natural environment and climate change to Covid-diary reflections: poetic urgencies in a new collection by Bernadette Mayer.

Milkweed Smithereens, by Bernadette Mayer,

New Directions, 85 pages, $16.95

• • •

An avant-gardist with a taste for Classics, a downtown poet who is unafraid of venerable forms such as the sonnet, Bernadette Mayer, born in Brooklyn in 1945, has long been adept at a kind of casually intimate conceptualism. The most celebrated example: her text-and-photo installation Memory. In July 1971, Mayer shot a roll a day of 35mm Kodachrome (“I literally, physically hated the other films”), and the following year exhibited 1,116 color prints, her handwritten notes, and a somewhat muffled recording of the artist-poet reading from the month’s journals. Constraint, series, grid: Memory seems very much of its rational artistic era, but is at the same time exquisitely hued, youthfully exuberant, and filled with instant nostalgia. All of which elements are (still) present in Milkweed Smithereens: a collection of new poems with others rediscovered in the poet’s attic and in the archive at UC San Diego—these alongside a prose(-ish) diary of pandemic isolation at her home in East Nassau, New York.

Mayer’s Covid Diary doesn’t so much punctuate the book, or frame the other works in it, as rush out among them here and there, like a partially culverted water course. In its lowercase, italicized flux, the diary is a reminder of John Ashbery’s well-known assertion that poetry is a constant babbling stream into which you simply dip a cup or ladle now and then. At one point in the diary Mayer says people have got it in their heads that poetry is easy—“the Frank O’Hara method”—and it is easy, “especially if you don’t try to say more than you are thinking.” What Mayer may be thinking, day to day, hour to hour, is not however at odds with formal ambition or complexity: her 1982 book Midwinter Day was all written in the course of a single December day, four years earlier. The journal as ritual structure, but also as healing force—in The Covid Diary Mayer announces: “this will be a little test to see if expressive (?) writing is a cure for the malaise of the coronavirus. well it doesn’t cure the pain in my left knee.”

Aged seventy-five in the first year of the pandemic, she admits to feeling nervous all the time but also does not care if she dies from Covid. And, anyway, death is always there, with its stupid lottery: “you might fall on your head or lightning strike you in the middle of the field. is a peafowl a peacock?” Some of The Covid Diary is merely exasperated: “the ides of june, 2020, & what a mess it all is.” Or seemingly despairing in the face of protracted disaster: “problem is, it has no end.” But a good deal more of this engagingly free-form, sometimes (formally) exacting, journal is also properly seething. From her rural home she rages at police shootings and police impunity. The fact of Donald Trump’s presidency squats over everything. Is he in fact the stink bug that time and again infests these pages? “The shadow of the bug is something to see,” Mayer tells us, and also “it’s surprising we have enough to eat given the stinkpotnesses of trump.”

But outside the house, in deepest lockdown, there is still—what? A version of nature, and nature poetry, that’s no simple consolation in a time of political, ecological, and viral catastrophe. Nature in these poems is by turns a rich historical archive (of threats and remedies) and a sort of revolutionary seedbed, a laboratory for propagating possible liberated futures. The title poem is short of line and spare in punctuation, but bristles with lore concerning the genus Asclepias: “herbaceous plants with a milky juice / showy flowers / more or less poisonous”—but edible when properly prepared. “A riot of milkweed close to the wigwam,” writes Mayer, paraphrasing the botanist Huron Smith in the 1920s, and thus conjuring a history of Indigenous knowledge and the colonial gaze on its holders. At times, in Mayer’s mind, nature is an invitation to knockabout eroticism, as in “The Joys of Dahlias”: “ahoy matey, I’m peeling your lollipop / dear darling and all that jazz.” In other places, a lush abandon has taken hold: “it’s in the midst of the pandemic, I think the red-winged blackbirds have taken over the western world, for humans the thing to do is stare.”

Although there’s much in Milkweed Smithereens to make one think of climate change and all the losses that come with it—ordinary seasonal transitions seem fraught: “so many leaves are / falling, it’s exhausting”—this work does not feel exactly, or merely, nostalgic. If there is a fond rather than furious retrospect here, it’s perhaps instead for the collective urgency of personal-political involvements from decades past. Frail hope in the present: “in catastrophes the best & most mutual-aidish is brought out in people—who needs governments.” But maybe such shared desires were always illusory? In “Star Wars,” the speaker imagines the untroubled ménage or throuple in which she’s involved becoming a life of collective poetic labor, writing pads on six knees, fearlessly advancing into the future. Or will they instead be “reported once by people looking at picture books / as a thing that happened around 1981 / among two crazy aunts and an uncle”?

And what of writing itself, the poetic adventure on the page? What value, what future? In “Wandering Scholars,” Mayer writes: “I left a perfectly good piece of equipment / behind under a bush. But I got away so what does it matter? / Let it go, I can find another one equally good here.” It’s a beautifully laconic image of what it might be like to have to write, day in, day out, with perfectly good equipment (talent, material, ambition) piling up uselessly behind you. Which is just the usual condition of writing. Mayer quotes Vladimir Nabokov, in The Gift: “I seem to remember my future works, although I don’t even know what they will be about.” In its newness, its remembrance, and its diaristic now, Milkweed Smithereens is a doggedly gorgeous expression of that peculiar, clairvoyant temporality.

Brian Dillon’s Affinities: On Art and Fascination will be published by New York Review Books in spring 2023. He is working on a book about Kate Bush’s 1985 album Hounds of Love.