The “Sunday Reads” section of the most recent edition of the British art magazine Elephant covers the newly Ashbery, Something Close to Music: Late Poems, Art Writing, and Playlists, part of Zwirner Books’ “ekphrasis” series, and the latest edition to the collected works of John Ashbery.

12 Jun 2022

Unfinished Business: The Captivating Afterlife of John Ashbery

A selection of late art criticism, poems, and playlists keeps conversations around the American writer’s legacy alive. Words by Adam Heardman

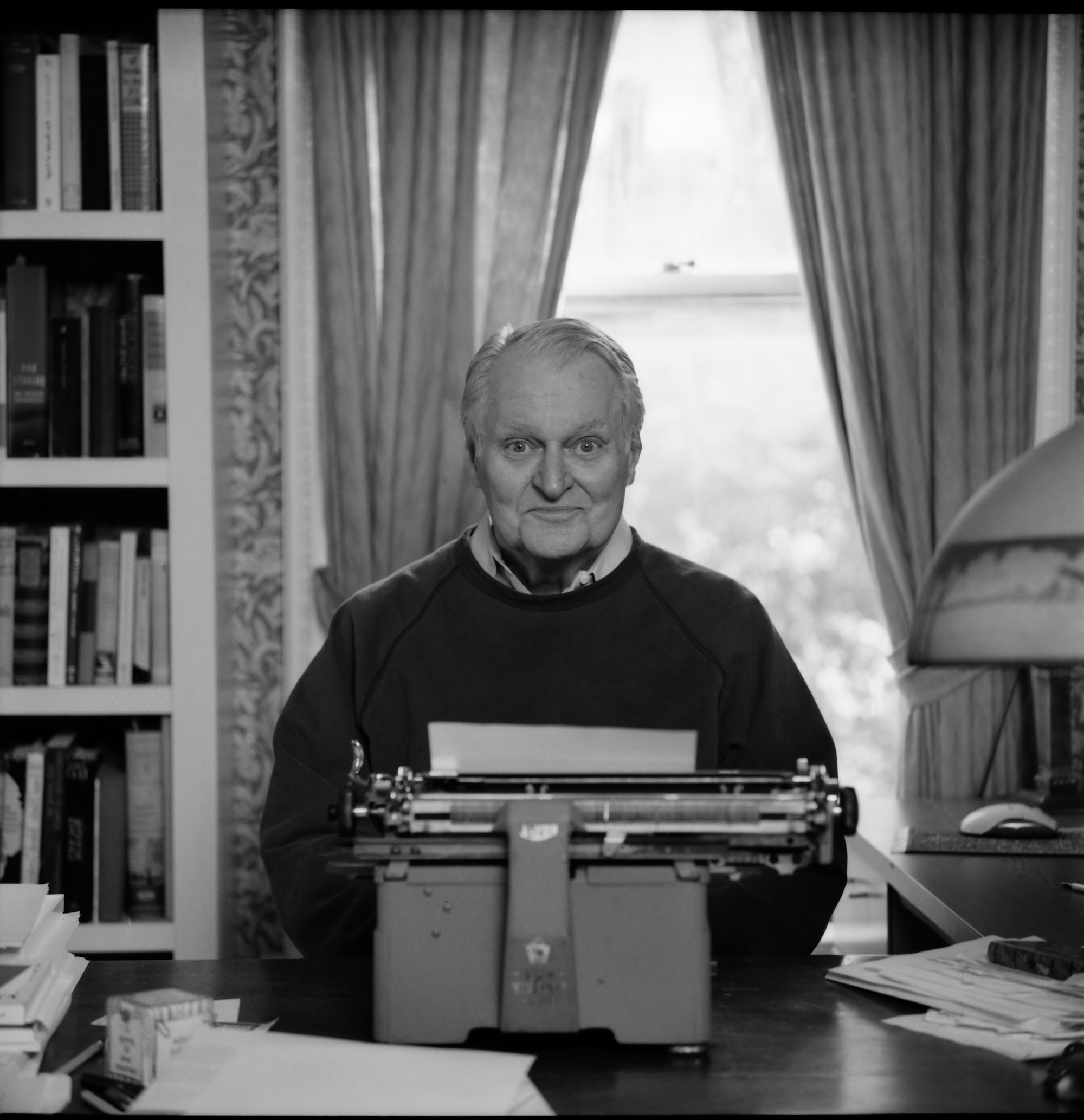

Exhibition of artworks owned by Ashbery.

“I was never interested in doing art criticism at all—I’m not sure that I am even now”, the poet John Ashbery told the Paris Review in 1983, 26 years into his career doing art criticism. “As so often when you exhibit reluctance to do something,” Ashbery continued, “people think you must be very good at it. If I had set out to be an art critic, I might never have succeeded”.

Barely hidden within Ashbery’s coyness is the admission that he did succeed as an art critic. It might be difficult to argue the contrary. (It was, after all, his job title for many years). Reported Sightings: Art Chronicles 1957-1987, compiling much of his work for ARTnews and the Herald Tribune, codified what was essentially Ashbery’s side-hustle into his canon. In 2022, however, a new volume takes a different approach to his legacy as poet-critic.

Something Close to Music is the third Ashbery book published since his death in 2017. It joins They Knew What They Wanted (2018), a collection of poems and collages released just months after his passing, and Parallel Movement of the Hands (2021), previously unpublished poems to which editor Emily Skillings attributes “a living, off-kilter quality”. The recurrence of the word ‘living’ in discussions of Ashbery’s posthumous work is noteworthy, testament both to his multivocal, multitemporal verse, and the difficulty of definitively summing-up this most uncatchable of poets. Ashbery remains unfinished.

In a 1989 essay included in Something Close to Music, Ashbery describes Yves Tanguy’s figures as being “of a type never encountered before yet palpably real, living if not breathing”. If, as Jeffrey Lependorf writes in his introduction, “the observations in his art writings also provide keys” to Ashbery’s own work, we can now begin to understand his response to art less as a ‘successful’ critical project, and rather something ‘living, if not breathing’, joining the poems in an ongoing afterlife.

The book presents art writing from Ashbery’s final years alongside poems chosen by Lependorf. A composer, Lependorf also includes playlists of music and classical recordings contemporaneous to the selected texts, inviting readers to discover how “music, poetry, and art writing, might illuminate and inform one another”.

A 1956 poem called The Painter (which doesn’t appear here) might be considered Ashbery’s opening statement on ekphrasis. It ends with the lines:

They tossed him, the portrait, from the tallest of the buildings;

And the sea devoured the canvas and the brush

As though his subject had decided to remain a prayer.

It’s a sestina, a form in which line-ending words recur with the awkward beauty of an algorithm. The portrait becomes a person, a ‘him’, but then washes away into the formless ocean, the future-orientation of ‘prayer’. Ashbery’s poetry uses language to dissolve ‘the subject’ into a recursive futurity. This is also, arguably, the project of his “criticism”.

“For Ashbery, ongoingness is more in tune with art’s (and nature’s) fundamental truths than completion”

Consider the following, from Reported Sightings, when Ashbery’s critical reading of Pierre Bonnard swerves into an anecdotal aside: “Bonnard once horrified guards in the Grenoble museum by going up to one of his own canvases and calmly proceeding to paint on it. And, in a sense, his paintings are unfinished, in the same way that nature is.”

Like the ever re-arriving words of a sestina, Bonnard “calmly” returns to the work, extending its life into the future, unaware that he has ‘horrified’ onlookers. For him, and Ashbery, ongoingness is more in tune with art’s (and nature’s) fundamental truths than completion.

Something Close to Music illustrates this by showing the germs of the poems inside the criticism. Lependorf picks moments when Ashbery’s prose begins to bubble at the rim, threatening to boil into poetics, using words that fizz and dazzle on the page—“mazelike”, “puluate”, “playacting”—then gives us the poems themselves (we see the word “playacting” slingshot from a 1995 note on Jane Frielicher’s painting into the later poem, Moderately).

Of John Adams’ music, Ashbery says that “in order for…outbursts of fresh invention to come about, the composer had to approach them through the back door of a self-imposed discipline”. Similarly, criticism is the ‘discipline’ through which Ashbery reaches ‘invention’.

Echoing Walt Whitman and nursery rhymes (“sings a song of thingness”), Ashbery builds the layered tonality of paint and music into his prose. Lependorf tells us that “Ashbery loved music and always listened to it while writing”. This comes out through the words, and is emphasised by the playlists.

Not all of Lependorf’s picks are winners. Bang on a Can’s rejig of Brian Eno’s Music for Airports is inessential listening compared with the original. Pop, key to Ashbery’s phonic palette, could also be better represented. But it’s a rich selection, decently approximating Ashbery’s rush of high and low registers, his simultaneous ear for melody and dissonance.

A practical difficulty of writing about Ashbery mirrors a potential problem with the book’s selective approach. Each time I highlight something from Ashbery’s texts, the flow of his writing holds my attention a few words further, chasing some essence that the lines keep pushing ahead of themselves/cresting into. I can’t catch it, and once again I’m instead simply reading John Ashbery, highlighting everything as I go.

“Ashbery’s poetry uses language to dissolve ‘the subject’ into a recursive futurity”

The only adequate illustration of Ashbery’s writing, it turns out, is Ashbery’s writing. The only sufficient extract is the whole line, then the next one, then the next one. Poetry is “a record of its own coming into being”, he writes. The flow is the meaning; quoting feels incomplete.

But then incompleteness is an essential part of the experience. The converse of this difficulty is, of course, that Ashbery’s writing rewards dipping in at random and beginning to read. Something Close to Music is as good a place as any to begin dipping. When we do, in the words of Ashbery’s poem Flow Chart:

At that point we’ll have lived, and the having done so would

be a passport to a permanent, adjacent future, the adult equivalent of innocence

in a child, or lost sweetness in a remembered fruit: something to tell time by.

Adam Heardman is a poet and writer from Newcastle upon Tyne currently based in East London

John Ashbery, Something Close to Music is out now (David Zwirner Books)